Read This Book!

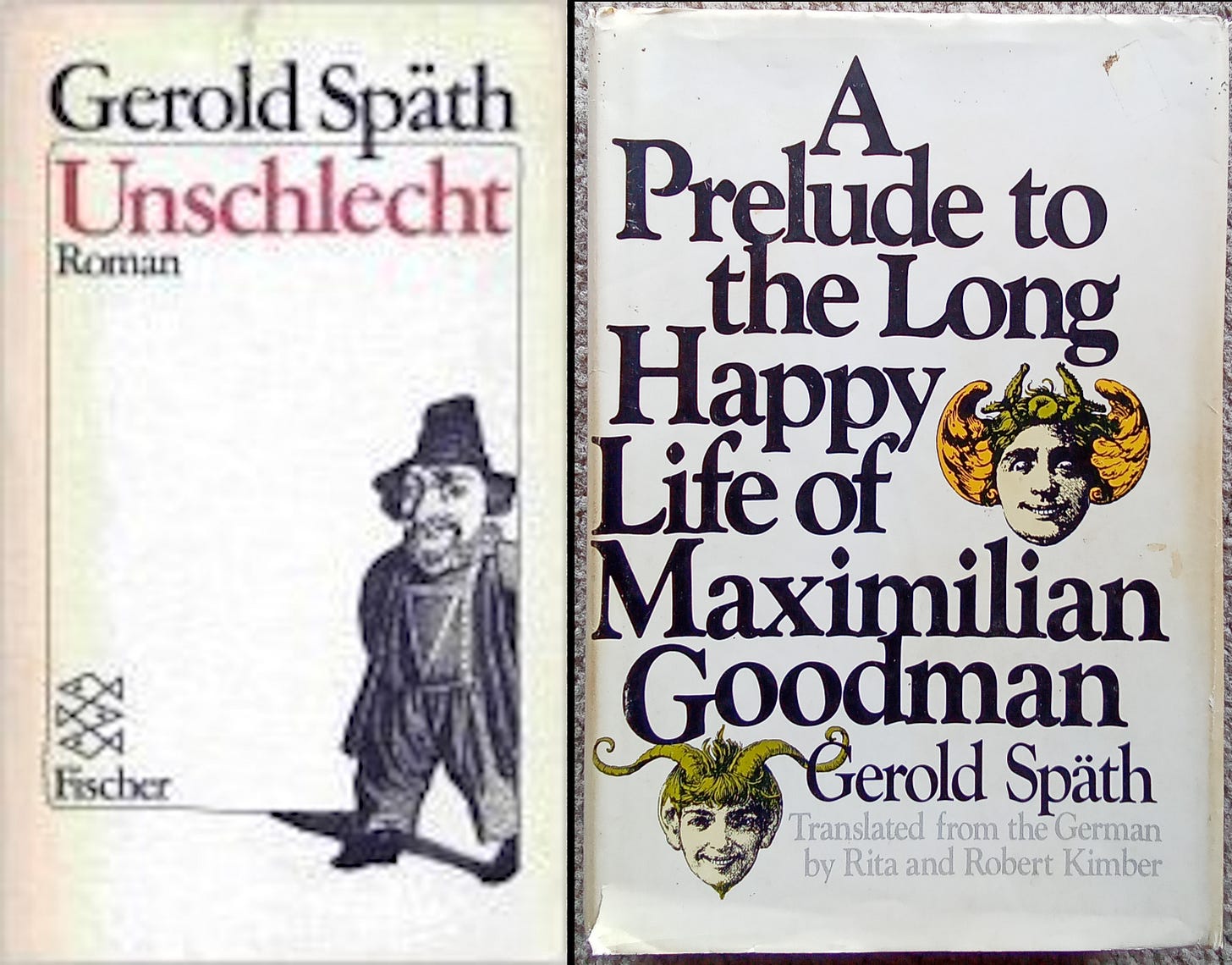

On Gerold Späth's "A Prelude to the Long Happy Life of Maximilian Goodman" ("Unschlecht,").

In a genre well known for weighing serious questions about life and the human condition, Swiss author Gerold Späth writes the funniest literary fiction I've ever seen. In 1975 Little, Brown published A Prelude to the Long Happy Life of Maximilian Goodman, Robert and Rita Kimber's English translation of his 1970 debut novel, Unschlecht. I found my copy in a bin of remaindered hardbacks at a drugstore in 1977, and for some forty-eight years I've guarded it like a family heirloom through eight moves around the USA and a tour in Germany while in the Army. To my surprise, it’s still in print and available through Amazon.

It's a pity that the rest of Späth's body of work hasn't been translated into English. I've read his other novels in the original German text, buying up copies when I can find them, and he's still writing. Everything short of maybe his grocery list written with bold strokes of comedy, this author is not afraid of going over the top.

The novel's protagonist, Johann Ferdinand Unschlecht has a name that's a play on words: Schlecht means bad in German, so Unschlecht literally means unbad, a backhanded way of saying good.

I was seventeen when I first read this novel, and I didn't come to fully appreciate Späth's talent until I was in my thirties, a little older, wiser, and more aware of the human foibles that he addresses so well. I've re-read the book several times over the years and keep finding new things each time I return to it. The characters and scenes in Rapperswil are familiar territory that have never left my memory.

On the first page, Späth minces no words as he sets the tone for what will follow:

It is not I but Zünd who exaggerates when he claims that this city has a total of twenty thousand inhabitants and that half of them, ten thousand, reside in the municipal madhouse. He likes to make pronouncements, likes to feel clever, my friend Zünd.

He is guilty of three exaggerations:

First, our city isn't really a city. It's just an overstuffed hamlet, a leftover Hapsburg citylet. Old documents carry on about a "strong, free city"; but grandiloquence wasn't unknown in those days, either; and as a rule, those old documents contain little more than fly-shit.

Second, Zünd overestimates the number of inhabitants. Exactly how many there are, not counting tourists and other vagrants, could only be determined hypothetically for any given day. People die and get born erratically around here. The lake plays havoc with statistics. Every summer has its share of unobtrusive drownings. Each victim tries to yell, strains to give tongue, can't manage, gasps, takes on water, loses track of his racing thoughts, goes under. That's something of a tradition around here. While one of us is on his way to Davy Jones's locker, somebody else is rolling his nymph in the bushes just a few yards from the water.

My friend is guilty of still another exaggeration, because third, our city has no municipal madhouse, nothing of the sort, doesn't need one. It would be superfluous.

When I made my first visit to Switzerland, I traveled directly to Lake Zurich and Rapperswil, Späth's home town and the setting for the story. I had to see this place for myself. During that trip in 1985 and a second trip in 2024, I had the opportunity to walk the streets of Rapperswil, a very charming small city on the eastern end of Lake Zurich, and visit the locations that I had read about. I saw the narrow back streets where schoolteacher August Meil ran naked through the night. I walked the harbor waterfront to see where Johann Unschlecht tied up his boat. I found the area where Renata, possessor of the finest breasts from Cremonia, ran her newspaper kiosk, although the kiosk and Renata were no longer there. I strolled around the rectory where Monsignor Ochs and housekeeper "Mouse" Klara lived. I stood on the shore by the old foundry and Au peninsula, where Paula Buchser washed laundry in the lake, and I drank beer outdoors at the Hotel Bellevue (today’s Hotel Schwanen), whose kitchen bought fresh fish from Unschlecht and was the site of numerous boozy episodes. From Rapperswil's harbor, the island where Unschlecht lived is clearly visible, as well as the channel that bisects it. According to the city, the channel was dredged out to make it easier for excursion boats to shuttle between Rapperswil's harbor and Zurich. According to Gerold Späth, Unschlecht creates the channel in a much more interesting way that I prefer to believe.

The novel is a sprawling, rollicking tale, covering some 435 pages in forty-nine chapters, and Späth has a gift for language, expertly turning a phrase and dialing up or dialing down the formality of his prose to set the mood, illuminate character, and enhance the humor. He doesn't write tight, but his skill with language makes the journey worth the time, like a John Irving novel, but 10x funnier. The story is narrated in the first person, looking back over the years as Unschlecht brings the reader up to the present, 1970 in this case. Having bought a paperback copy of Unschlecht, readily available in Germany and Switzerland, and seeing Späth's story in the original German text, I'd say that the Kimbers's translation is very faithful in capturing this author's voice and artistry.

The story opens with Unschlecht coming of age and taking possession of the inheritance left to him by his long dead artist father. His foster parents, Justice of the Peace Xaver Rickenmann and wife Frieda, did what they could to raise a boy who would otherwise behave more like a captive wild animal, and by his teen years, Johann moved onto his family's island on Lake Zurich by Rapperswil to look after himself. Never getting past third grade, he'd rather fish in the lake than study. A local fishermen, old Pankraz Buchser takes him under his wing to teach him the ways of Lake Zurich, raising him, and young Unschlecht earns an adequate living as a small-time commercial fisherman.

Now that Unschlecht has access to the several million francs his late father left him, he makes a memorable visit to the local branch of the First Cantonal Bank and Trust Company of St Gall and politely demands that they let him look at his money. All of it. This sends bank president Honegger into fits of apoplexy every time Unschlecht mentions transferring the funds to another bank. After a hastily-arranged trip to the main vault to let Unschlecht view his fortune, they compromise by setting him up with a checking account and a small withdrawal, which Unschlecht takes in the form of fifty ingots of gold bullion.

He stops at the home of his foster parents, Xaver and Frieda Rickenmann and gives his Aunt Frieda a gold ingot:

Aunt Frieda acted quickly and adroitly. In one motion, she snatched up apron, skirt, and slip. Her thighs, exposed at maximum circumference, bulged doughy-white and varicose above her stockings. With her free hand, she pulled the elastic waistband of her pants away from the white dome of her belly and dropped my offering of gold, deftly but without haste, into the depths below. "Xaver will never find it there," she said. Belly, underpinnings and underpants all disappeared instantly under her skirt and apron. No one would have guessed that cool gold lay buried between the legs of Frieda Rickenmann, wife of Rapperswil's justice of the peace.

Word spreads fast about his fortune, and like a lottery winner, all kinds of people descend on Johannes Unschlecht, drawn by the scent of his money. Everybody from his foster parents to the parish priest wants to be his friend, give him advice, and take a piece of the Unschlecht fortune.

This drives much of the plot in the first half of the novel, as parish priest Ochs persuades Unschlecht to buy numerous kitschy art objects that had been moldering in the church's cellar at the bargain price of 56,500 francs. Unschlecht had taken a liking to a life-size plaster crucifix, and Monsignor Och's power of persuasion, coupled with the two bottles of wine they drank during the negotiation, helped close the package deal and clear out clutter from the church cellar.

Several instances of magic realism occur in the novel. In the first Buchser hands Unschlecht a dead fingerling pike wrapped in wax paper before the town's Corpus Christi parade begins. He instructs Unschlecht to dunk it in holy water while squeezing a gold ingot in his other hand and saying: "Fish in the water, fish in the street, fill our nets to bulging." During the parade, as Unschlecht marches with the other fishermen, his pockets begin to fill with live, wriggling pike. He hands off fistfuls to his fellow fishermen, whose pockets soon cannot hold any more. More fish appear in his pockets, slide down his pants, and after a few minutes, Unschlecht has deposited hundreds of live fish onto the street. He makes a panicked retreat to the lake, and the next day's newspaper reports over 200 pounds of fish spilled onto the parade route, a malicious prank.

A few days later, Pan Buchser's wife, Paula loses her footing while laundering clothes in the lake, doesn't know how to swim, and drifts out to the deep water. The other women out there laundering clothes spot a wizened, arthritic old man in hip waders fishing nearby, and they descend on him, ordering him to swim out to save Paula:

They shouted him down, surrounded him, pressed in on him, that limping, coughing figure with inflamed pig eyes in his wrinkly face. They forced him into a pathetic attitude of defense. There was no escape for him. The washerwomen came down on him like a landslide, drove him past the tables, onto the dock, pushed him out to the edge, step by step. They terrorized him, jostled him, prodded him with bellies, boobs, and massive washwomanly legs. And when he tried to break away, they pressed in even closer and closer, shoved him mercilessly into the water. Then they jumped back from the splash.

Unschlecht's friend, Zachi Zünd, hears the commotion, recognizes that Paula Buchser is screaming and drowning.

He reconsiders. In this case, he'd better be a man; he'd better show that stuff he's made of, though not the way he shows it in some waitress's attic bedroom. He ran to the mouth of the creek and tore off his clothes like a man. No one saw him slip into the water in his nakedness. But everyone saw the courageous swimmer paddling out into the brown currant. And everyone breathed a sigh of relief, especially the little old man on his slippery concrete block. Now he could climb back onto the shore unnoticed, take off his bulging, water-laden boots and empty them over the embankment. And after all the spectators had sighed their sighs of relief, they held their breaths again and stared bug-eyed across the water.

But alas - and here our long and mournful dirge begins - alas and alack, in this suspenseful and hopeful moment, no more could be heard from our lonely washerwoman in her life-preserving skirt. No speck of light blue could be seen, no speck of dark blue, no thrashings in the water, nothing could be seen at all except Zünd's head, helplessly spitting water. Paula Buchser had ceased her fruitless, unanswered cries. Quiet settled over the Foundry. Only Rapperswil Creek could be heard, swirling, eddying, gurgling, stinking to high heaven as usual.

From time to time, Späth follows the path of the submerged body as it drifts among the fish and currents of the lake. Paula Buchser may no longer be among the living, but she remains in the story. What would ordinarily be a tragic event becomes comedic as Späth tells it.

Magic realism appears several times later in the story, all at the hands of Pan Buchser. The old man forms a partnership with Unschlecht, selling and delivering good weather to order for Rapperswil's various civic groups. After Buchser loses his Paula to drowning, he moves onto Unschlecht's island in the middle of the night, conjuring up a dozen ghosts to help with ferrying his belongings on rowboats: furniture, a milk cow, and several pigs join Unschlecht and Buchser on the island.

The novel is loaded with other memorable scenes that stay in the reader's memory long after putting the book away: Pan Buchser losing his temper and summoning a storm over Lake Zurich, Unschlecht's encounter with a cult after he meets Mademoiselle Cleo, the aforementioned Corpus Christi procession and Buchser conjuring up ghosts, schoolteacher August Meil running naked through the streets of Rapperswil late at night, Justice of the Peace Xaver Rickenmann taking Unschlecht to his favorite Zurich gay bar and its floor show, the very curvaceous Renata gnawing on a gold ingot while Unschlecht peers down her cleavage to admire the finest breasts to come out of Cremonia, along with Unschlecht blasting a chunk of his island away with several cases of stolen dynamite, and more.

Unschlecht eventually comes to believe that too many people in Rapperswil are only interested in his money, and he makes preparations to leave in a big way. He starts with a watertight safe packed with cash and a few pornographic postcards bought from Renata that he sinks to the bottom of Lake Zurich for later use. Johann Unschlecht may not be book smart, but years of fending for himself on the lake have provided him with plenty of street smarts.

The late Paula Buchser makes her final appearance, and Unschlecht puts her to work guarding his sunken safe. He takes his stash of money and dirty pictures from the safe and leaves for Zurich in the dead of the night, while a fuse burns its way down to the dynamite hidden in his cellar. The blast bisects his island and provides more than enough cover for his departure from Rapperswil.

Once in Zurich, Unschlecht makes the acquaintance of James Kuster and acquires three forged passports. This marks the beginning of his alter ego and future identity as Maximilian Goodman. From Zurich, he makes his way to London via stopovers in Geneva and Paris. In London, Unschlecht, now as Goodman and sporting a full beard, rents a very modest flat and cools his heels for two months as he takes English lessons.

Unschlecht begins the process of reinventing himself, and as the character discusses the topic of transforming his identity from the rough-hewn "Island Hannes" to the sophisticated Maximilian Goodman, I see Späth giving a nod to fellow Swiss author and contemporary, Max Frisch. Like Max Frisch's Gantenbein character in A Wilderness of Mirrors and Stiller in I'm Not Stiller, Johann Unschlecht wrestles with the question of just who he really is and who he wants to be. The main difference between the two authors is that Max Frisch makes me think, and Gerold Späth makes me laugh.

Unschlecht, now as Goodman, makes his way to Hamburg and after reading the personal ads in the newspaper, writes a letter in response to an advertisement from a widow seeking a companion for her daughter. He receives an answer, which in turn leads to a meeting in Berlin with Benno Schaumberger, the attorney representing the widow who placed the personal ad. In time, the two make their way to the family castle, Katzenstein, in southern Germany, and Goodman is introduced to Widow van Boers and her daughter, Isabella Sibylla Sunneva. The daughter is heir to the considerable van Boers fortune, has the face of a pig, the body of a pin-up model, and the mind of a five-year-old. Of course Goodman agrees to marry her.

Behind the scenes many more things are going on as Goodman settles into his new role and struggles with keeping Unschlecht under control. He married Sibylla as part of his plot to reinvent himself and for the family fortune. Goodman maneuvers his way into managing the family's businesses and extensive wealth. Schaumberger presses him to sire a family heir, which Goodman halfheartedly pursues. Sibylla has no personality to speak of, and he'd rather continue fornicating Sibylla's nurse, two maids on staff, and the occasional barfly picked up in nearby taverns.

After a convenient accident takes Schaumberger out of the picture, Goodman considers his situation: he effectively has control over all of the van Boers fortune. If something were to happen to Sibylla, he would own it all as her husband and sole heir. Maybe he doesn't need her any more.

Late one afternoon, Goodman's walk on the grounds is interrupted by shrieks. Sibylla has fallen into the duck pond and can't swim. Reflexes take over, and it's Unschlecht who jumps into the water. The same Johann Unschlecht who expertly swam underwater in Lake Zurich to untangle fishing nets and retrieve fouled anchors now swims to the bottom of the pond to save Sibylla and perform artificial respiration on the shore.

As much as he'd like to shed and abandon "Island Hannes" Unschlecht, Goodman finds that he still needs his old identity, that Unschlecht has native capacity to understand, to love and appreciate Sibylla, to know that life is as goodgoodgood as she says.